I am presently working on two articles centered on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. They expand on the chapter of my first book project that examines Christmas Islanders’ citizenship claims after the transfer of the island’s sovereignty from British-colonial Singapore to Australia in 1958. It argues that their contested citizenship statuses resulted from the island’s suspension in various legal states of exception, most crucially as an Asian-majority territory of Australia when exclusionary White Australia policies were still in effect. In particular, it critically engages with the notion of “quasi-indigeneity,” a term coined by Australian officials to denote Malay, Chinese, and Eurasian islanders’ ambiguous status somewhere in between migrant and indigene.

This project asks how seemingly peripheral island spaces and the complex racial formations associated with them might help us rethink canonical understandings of the mid-twentieth century as a so-called “era of decolonization.” When viewed from the vantage point of this guano island, the atrophy of British imperial power in Southeast Asia proceeded in lockstep with the surge in Australia’s prominence as the Western Bloc’s regional policeman. Islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans were stringed together as a joint security concern, with Christmas Island yoked in Australian imperial geography to other phosphate islands like Nauru and Banaba in Kiribati. Situated at the intersection of social history, environmental history, diplomatic history, and the history of international law, the project tracks how imperial formations were made anew after decolonization.

The Quasi-Indigenous of Christmas Island

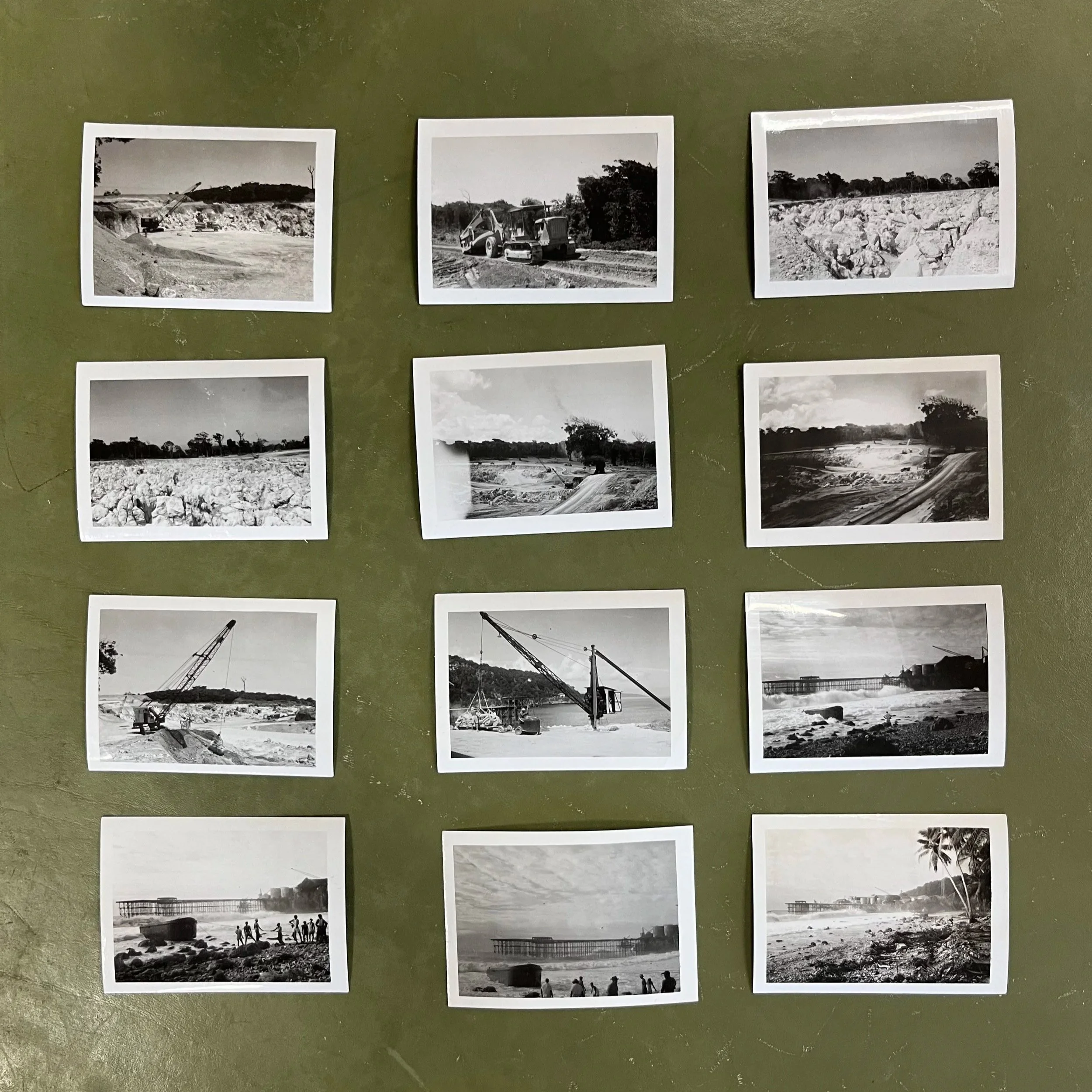

Photographs of the phosphate works on Christmas Island appended to a December 1950 report for the British Phosphate Commissioners